12/27/25

Interview & Edit & Translation: Sara Hirayama

Photography: J.K Chekpo & Musashi & Hinata Ishizawa

人はみな、気づかないうちにその土地や環境の情報を体全体で吸収している。

東京でフォトグラファーとして活動していたHinata Ishizawaは、現在ベルリンのエネルギーを浴びながら制作を続けるビジュアルアーティストだ。そんな彼が2025年夏に開催した初の展示 “Mela-Tri” では、移住からの5年間で探求してきたアイデアを、存在表明ともいえるかたちで披露し、多くの来場者を集めた。写真というメディアを起点に、「データ」「記憶」「無意識」といった目に見えない領域へと拡張されていく思考のプロセスに焦点を当てる。このインタビューでは、ベルリンでの生活やキャリア転換を経て今に至る彼に、手を動かす感覚を頼りにたどり着いた表現と、その背景にある思考や制作について聞いた。

People absorb information from the land and environment around them with their entire bodies, often without conscious awareness.

Hinata Ishizawa, a former photographer based in Tokyo, is now a visual artist continuing his artistic expression while immersed in the energy of Berlin. In his first exhibition, Mela-Tri, held in the summer of 2025, he presented ideas he had explored over five years since relocating – almost as a declaration of existence – drawing a large number of visitors. Starting from photography as a medium, his work focuses on a thought process that expands into invisible realms such as “data,” “memory,” and the “unconsciousness.” In this interview, we explore the ways of expressions he has developed by trusting his skill of working with his hands along with ideas and creative processes behind them, shaped through life in Berlin and shifts in his career.

◻︎ まずはHinataくんのことを知らない人に向けて、自己紹介をお願いします。

ベルリンを拠点に活動しているビジュアルアーティストのHinata Ishizawaです。出身は新潟県の津南町っていうすごい田舎なんですけど、ベルリンに来てからもう5年ぐらい経ってます。1994年4月5日生まれの牡羊座です。

元々写真をやっていて、東京の代官山スタジオで主にファンションの現場の撮影アシスタントをしていました。そのあとドイツ・ベルリンに来て、しばらく写真の仕事をしてたんですけど、コロナを機にちがう方向に行きたいなと思って。それでいろいろ作りはじめたのがきっかけで、今はビジュアルアーティストとして活動をしています。

写真って人のなにかを記録するものだけどで、本当は物質的なものがデータに置き換わってるっていう現実を目の当たりにして、写真を広い定義でデータとして捉え、「データと記憶」をテーマに制作をしています。

◻︎ First, for those who may not know you, could you introduce yourself?

My name is Hinata Ishizawa, and I’m a visual artist based in Berlin. I’m originally from Tsunan-machi in Niigata, which is very much a rural area, and I’ve been living in Berlin for about five years now. I was born on April 5, 1994, so I’m Aries.

I originally worked in photography and was mainly assisting on fashion shoots at Daikanyama Studio in Tokyo. After that, I moved to Berlin, Germany, where I continued working in photography for a while. During the COVID period, though, I started feeling that I wanted to move in a different direction. That led me to begin making various kinds of work, which is how I arrived at my current practice as a visual artist.

Photography is a medium that records something about people, but at the same time, we’re living in a reality where material things are being replaced by data. Confronting that fact led me to think of photography, in a broader sense, as data itself. Since then, I’ve been creating work around the theme of “data and memory.”

◻︎ ビジュアルアーティストとしての経歴は?

あんまり長くはないけれど、写真からちょっとちがう方向にいったのは2022年ぐらいからかな。そのぐらいから制作をはじめて、いろんなグループ展だったりに参加して、今年初めてベルリンで個展をした。デジタルアートって見られがちなんだけど、フィジカルな作品をずっと作ってる。

最近はパフォーマンスアートの人とコラボレーションして、ライブビジュアルを作ったりとか、そういうこともしつつ。今はインスタレーションの作品も作りはじめてるところなんだけど。今まで2Dだったものから、来年は表現の幅を広げていけたらいいなと思ってる。今でもちょいちょい写真撮る仕事はあるんだけど、自分の作品を作ることにフォーカスして、って感じかな。

◻︎ What is your background as a visual artist?

It’s not very long, but I’d say I started moving in a slightly different direction from photography around 2022. That’s when I started creating artwork, participating in various group exhibitions, and this year I held my first solo exhibition in Berlin. People often assume my work is digital art, but I’ve consistently been making physical, tangible pieces.

Recently, I’ve also been collaborating with performance artists, creating live visuals and working on projects like that. I’ve started developing installation works as well. Up until now, my practice has mostly been two-dimensional, but next year I’d like to expand my range of expression even further. I still take on photography jobs from time to time, but my main focus is on creating my own work.

◻︎ デジタルとフィジカル、Hinataくんにとっての大きなちがいとは?

デジタルって奥行きがあるように見えるけど、実際画面を通してしか見えない平面のもの。でもフィジカルなものって、奥行きがあって質感が見えるっていうか、そのちがいがあるかなって思う。

僕の作品もインスタで見たらデジタルアートなのかなって思われがちなんだけど、実際近くで見てみるとテクスチャーがあったりとか、凹凸があったりとか。スリーダイメンショナル(3D)な形をしているのがデジタルとフィジカルの大きなちがいだし、そこが面白いところかなって。形をもってるかもってないか。

◻︎ For you, Hinata, what is the biggest difference between digital and physical work?

Digital work can appear to have depth, but in reality it’s something you can only see as a flat surface through a screen. Physical work, on the other hand, has real depth – you can perceive its texture and materiality. That’s the key difference for me.

When people see my work on Instagram, they often assume it’s digital art, but when you see the work in person, you can experience the textures and the uneven surfaces. The fact that it exists in a three-dimensional (3D) form is the major distinction between digital and physical work, and that’s what I find interesting about it. Whether something has a physical form or not.

◻︎ 自己表現において意識してることはなんですか?

意識してるって言われたらちがうかもしれないけど、結局僕って飽き性で、自分が楽しいなって思ってないと作れないから。浮かんできたアイデアをいかに自分が楽しめるかたちにするか。作り方とか、アイデアに対してアプローチをしてる自分が作ってて楽しいかなとか、そういうことは意識してるのかなぁ。

昔からレゴブロックとかガンプラとか、細かい手作業が好きで。ようはデジタルアートってパソコンでかちゃかちゃやるだけ、よりかは実際に手を使って切って貼って組み立てるほうが僕は楽しくって。写真やる前は飴細工とかしたくてパティシエとして働いてて。

写真だけだったら、今振り返ってみてもそんなに楽しくなかったなぁみたいな。楽しいし好きだけど、写真ってシャッター押したら撮れちゃうし、それだけじゃ自分のクリエイティビティが満足してなかったのかなとは思う。

◻︎ What do you consciously keep in mind when it comes to self-expression?

If you ask what I’m conscious of, it might not be the right way to put it – but the truth is, I get bored easily, and I can’t create anything unless I’m genuinely enjoying myself. So I think about how I can turn an idea that comes to me into something entertaining for me. Whether it’s the method of making, or the way I approach an idea, I value whether I’m enjoying the process while I’m working.

I’ve always liked detailed, hands-on work, such as LEGO bricks or building Gunpla (Gundam plastic models). Basically, compared to digital art where you’re just clicking away on a computer, it is much more fun actually using my hands to cut, paste, and assemble things. Before I got into photography, I wanted to do sugar art and worked as a pastry chef.

Looking back now, working only with photography wasn’t that enjoyable for me. I like it and I enjoy it, but with photography, once you press the shutter, the image is captured – and I think that alone wasn’t fully satisfying my creativity.

◻︎ 人生が変わった出来事をあげるとしたら?

ベルリンに来たことが大きな人生の転換だったかなって思う。来た時期もちょうどコロナの直前、2020年の1月とかだから、時間はたくさんあった。ロックダウンしてたし、仕事もないし、貯金もないから遊び行くもないし。そのときに自分の人生とか、なにをしたいかについてとか、いろんなことを考えた結果、今の自分がいる。ベルリンに来てなかったらこういう表現してなかったし、興味すらもってなかったかもなとかも思う。自分の人生において一番大きな転換は、ベルリンに引っ越してきたことかな。

◻︎ If you had to name an event that changed your life, what would it be?

I’d say moving to Berlin was a major turning point in my life. I came here just before COVID – around January 2020 – so I had a lot of time to myself. There was a lockdown, no work, no savings, and nowhere to go for fun. During that period, I spent a lot of time thinking about my life and what I really wanted to do, and that reflection led me to where I am now. If I hadn’t come to Berlin, I probably wouldn’t be making the kind of work I do today – or even have had an interest in it at all. So for me, the biggest turning point in my life was moving to Berlin.

◻︎ ベルリンと東京のちがいとは?

視覚的にいうと、特に東京でフォトグラファーのアシスタントをしてたときは、写真を見ることが多いと感じた。街中でも広告に写真がたくさんあったし、雑誌もいっぱいあったし、写真がそこらじゅうにあるような生活をしてた。けど、ベルリンの街中に写真はあんまりないけど、その代わりグラフィティがめちゃくちゃ書かれてたりとか、グラフィックアートがもっと身近にある。僕すごい影響受けやすいタイプなんだよね。ベルリンに来たからこそ、街中のグラフィティとかから刺激を受けて、今みたいな表現の方向にいったのかなみたいな。

聴く音楽とかも変わったしね。日本にいたときもエレクトロミュージック好きだったけど、今ほど聴いてなかった。東京にいたときに聴いてたシティポップとかヒップホップとかは聴かなくなったし。今じゃアンビエントとかエレクトロミュージック、静かなミニマルテクノとそのへんしか聴かない。

◻︎ How is Berlin different from Tokyo?

Visually, when I was working as a photography assistant in Tokyo, I felt like I was seeing a lot of photos everywhere. There were photos in advertisements all over the city, magazines were full of them – it felt like I was living in a world saturated with photography. In Berlin, you don’t really see that many photos in the streets, but instead, there’s graffiti everywhere, and graphic art is much more present in everyday life. I’m the type of person who’s really easily influenced, so being in Berlin and seeing all that street art probably inspired me to develop the way I express myself in art today.

The music I listen to also changed. I liked electronic music back in Japan, but I didn’t listen to it as much as I do now. I stopped listening to city pop and hip-hop like I used to in Tokyo. Now, I mostly listen to ambient, electronic music, and quiet, minimal techno – things along those lines.

◻︎ 今年の夏に行ったベルリンでの個展 “Mela-Tri” について聞かせて!

今年から取り組んでたシリーズで “The Silhouette of Dreams” 、日本語訳で「夢の輪郭」ってあったんだけど。写真からビジュアルアートに移って以来、自分のなかである程度いい到達点にきたなって思えるもので。使ってるメディア(素材)自体は写真のままなんだけど、写真の解釈が納得いくかたちに変わって表現できた作品だったから、それで展示をしたいなって思った。けっこう凝り性だから自分の納得いくものができるまであんまり展示したくないっていうのがあって。やっと人に自信をもって見せれるなっていう感じ。

“The Silhouette of Dreams” について話すと、人ってなにを夢みるかっていうのはコントロール(操作)できないけど、夢って自分の経験とか記憶からくる部分が大きいと思うんだよね。自分のハードディスクのなかにいっぱいある写真が、夢に出てくる記憶との存在に似てるなってふと気づいた。たまに自分でも覚えてないような風景が出てきたりとか、覚えてないような場所に行くことってあると思うんだけど、それと一緒で自分でも撮ったこと覚えてないような場所がハードディスクのなかにいっぱいあって、それを使ってなにかできないかなって思ったのがきっかけ。

夢は自分で編集することができないように、自分でコントロールできない編集を使って新しい画像を作るっていうのがはじまり。書き出しするまで結果が見えないようになってる音楽編集ソフトで写真の編集をするっていう技術をたまたま見つけて。なんとなく自分の脳で夢をみるときのプロセスと似てるのかなって思って。それで写真を編集しはじめたんだけど、デジタルでやってるだけじゃつまんなかったから、さらに自分でなるべくコントロールしないように切ったり貼ったりしたっていう作品。ディスクリプション読んで(笑)

◻︎ Tell us about Mela-Tri, your solo exhibition in Berlin this summer!

The exhibition featured a series I started working on this year called The Silhouette of Dreams, or Yume No Rinkaku in Japanese. Since shifting from photography to visual art, this series felt like an important milestone for me. The medium is still photography, but I was able to reinterpret and present the photos in a way that felt satisfying, which made me want to exhibit the work finally. I tend to be very meticulous, so I usually wait until I feel fully satisfied before showing anything. This has reached the point where I could confidently share with others.

The concept of The Silhouette of Dreams comes from the idea that people cannot control what they dream about, but dreams are largely shaped by personal experiences and memories. I realized that the many photos stored on my hard drive are similar to how memories appear in dreams. Sometimes you experience a scene in a dream that you don’t consciously remember. Similarly, there are many photos on my hard drive of places I had forgotten. I wondered if I could create something new using these forgotten images.

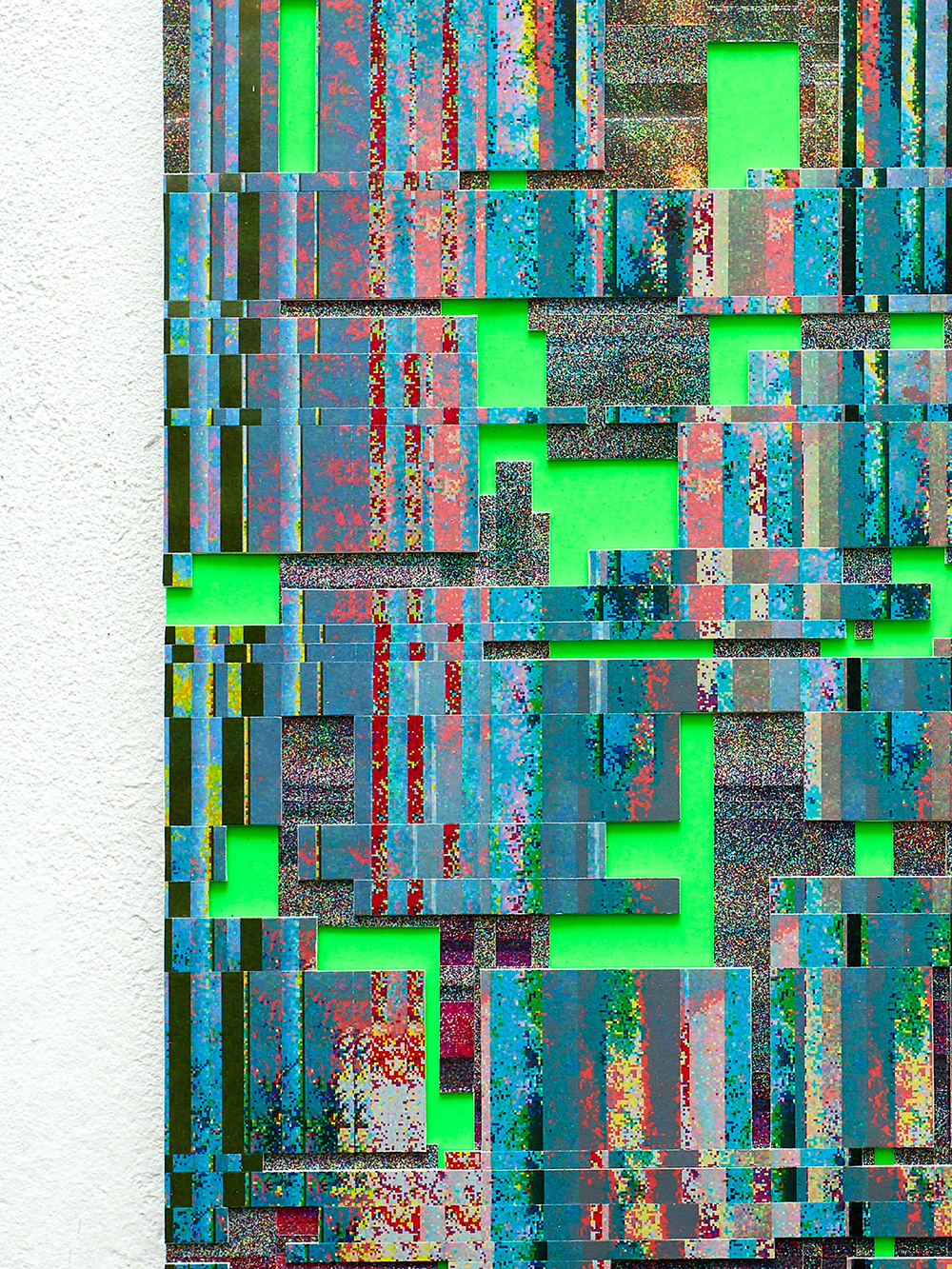

Since we cannot edit our own dreams, I started generating new images through an uncontrollable editing process. I discovered a technique for editing photos in music editing software, where you cannot see the result until you export it. This process felt similar to how the brain experiences dreams. At the same time, just doing it digitally felt a bit boring, so I also physically cut, pasted, and assembled the images while trying not to control myself too much. You can read the description for more context, haha.

The Silhouette of Dreams

2025本シリーズは、現代のデータ社会における情報の流れと、人間の無意識下における意識の流れの共通性に着目することから始まった。写真を「記憶の断片を含んだデータ」として再認識し、音声編集ソフトを用いて意図や制御から離れた編集を施すことで、新たなイメージの生成を試みている。得られた画像はプリント後に細かく裁断され、モザイク状に再構成される。さらにランダムに欠落を加えることで、記憶の曖昧さや断片性を想起させる。こうして構成された複数のレイヤーは、断片と空白が交錯する新たな視覚的パターンを生み出す。本作は、無意識下に潜む記憶のかたちを視覚化し、「夢」という意図や制御を超えて内側から生まれる現象の輪郭をなぞる体験を通して、鑑賞者に個人的な記憶やイメージとの接続を促すことを試みている。

This series began by exploring the parallels between the flow of information in today’s data-driven society and the invisible currents of the human unconscious. Rather than treating photography as a visual record, the medium is reinterpreted as data embedded with fragments of memory. By editing photographic material using audio software —removing intention and control from the process—the work invites unexpected forms to emerge. The resulting images are printed, finely cut, and reassembled into mosaic-like structures. Portions of the image are then deliberately removed at random, evoking the inherent ambiguity and fragmentation of memory. Through layering these altered fragments, a visual field takes shape in which absence and discontinuity intersect, giving rise to new patterns. This series aims to offer a visual experience that gives form to memories that reside unconsciously at the depths of our awareness.It focuses in particular on dreams—phenomena that arise beyond will or control—and seeks to trace their indistinct outlines, prompting the viewer to connect with their own personal memories and inner imagery.

◻︎ Hinataくんの作品を見た人にどんなことを感じてほしい?

自分たちの意識の流れってすごい神秘的なものなのに、みんな気づいてない。普通に生活してたら気づかないじゃん。それに気づくチャンスを与えられたらなと思う。

僕は映画監督の今 敏が好きで、すごい印象的なインタビューがあるんだけど。彼がメルボルンかどっかにいたときに、東京の人にメールでインタビューされてるみたいな。東京に向かってメールを書いてるときに自分の意識が “東京” に引っ張られる。僕はこれをマインドフローティングって呼んでるんだけど。自分の脳みそのなかで「東京=誰」「東京=どこ」って勝手にぽんぽん結びついてどんどん進んでくじゃん。そういうことを今 敏は表現したいってインタビューで言ってた。

自分でコントロールできない意識の流れって絶対あると思うんだよね。例えば、ご飯食べてるときに嗅いだ味噌汁の香りで実家の味噌汁を思い出す。したら実家の風景が思い浮かぶじゃん、意識せずとも。そこから「実家」に引っ張られて「お母さん元気かな」とか。そうやって自分がコントロールしてない意識の流れって絶対あると思うんだよね。すごい人間らしいものだなって僕は思ってて、だからそれを表現したい。自分たちの意識ってすごい神秘的な動きをしてるもんなんだよねっていうのを気づかせるって言ったら大袈裟だけど、感じとってくれる作品を作れたらいいなって思ってる。

◻︎ What do you want people to feel when they see your work?

Our flow of consciousness is incredibly magical, but most people don’t notice it. In everyday life, we just don’t pay much attention. I hope my work can offer a chance to notice it.

I really like the filmmaker Satoshi Kon, and there’s a particularly memorable interview of his. When he was in Melbourne – or somewhere like that, he was being interviewed by someone in Tokyo via email. As he was writing emails directed at Tokyo, his consciousness was pulled toward Tokyo. I call this mind floating. In your brain, “Tokyo = someone” and “Tokyo = somewhere” automatically start connecting and evolving on their own. Satoshi Kon said in that interview that he wanted to express this kind of process through his work.

I believe there is always a flow of consciousness that we cannot control. For example, when you smell miso soup, it might remind you of the miso soup back home. Immediately, images of your home might come to mind without you trying. That could then lead to thoughts like, “I wonder how my mother is doing.” This flow of consciousness that we don’t control is very human, and that’s what I want to express. It might sound exaggerated to say that my work makes people notice how mysterious our consciousness is, but I hope my pieces can convey that feeling.

◻︎ 人生に変化はつきものだけど、貫き通してる信念や座右の銘があったら教えて。

座右の銘は、2つぐらいある。「先の先から今を考える」みたいな。将来から逆算して今の自分を考えるようにはしてて。将来こういう人になりたいとか、こういう目標があるから今の自分はなにをしなきゃいけないとか。将来の自分に置き土産をするじゃないけど、将来の自分のためになにかをしておこうみたいなことはすごい考えてるかも。

あともういっこ、これは僕の腕にタトゥーでも入ってるんだけど “Pain is inevitable. Suffering is optional.” 「痛みは避けられないけど、それに苦しむかは自分次第ですよ」みたいな。元々チベット仏教かかなんかの言葉なんだけど、村上春樹が小説かなんかで取り上げて、ちょっと有名になった言葉らしくって。パティシエの仕事を辞めたタイミングでこのタトゥーを彫ったんだよね。ヒルトン東京ってホテルで就職したのよ。そこで2、3年ぐらいパティシエやってた。

◻︎ Life is full of changes, but do you have any guiding beliefs or personal mottos that you stick to?

I have about two personal mottos. One is something like, “Think about the present from the perspective of the future.” I try to see my current self by working backward from the future. For example, if I want to become a certain kind of person or have specific goals in the future, I think about what I need to do now. It’s like leaving something for my future self – I think a lot about doing things now that will benefit me later.

The other one is a quote I even have tattooed on my arm: “Pain is inevitable. Suffering is optional.” It roughly means, “Pain can’t be avoided, but whether you suffer is up to you.” The phrase originally comes from Tibetan Buddhism or something like that, but it became a bit famous after Haruki Murakami mentioned it in a novel. I got this tattoo when I quit my job as a pastry chef. I had been working at the Hilton Tokyo hotel as a pastry chef for about two or three years.

◻︎ なぜお菓子作りの道へ?

僕の高校が進学校だったんだけど、大学行くことが当たり前みたいなところに反骨心があったのか、そういう風潮に逆らいたくって。今では大学行っときゃよかったみたいに思うんだけど。親が料理好きで、ちっちゃい頃から俺も料理は好きで、なかでもお菓子作りが。毎年自分でクリスマスケーキ作ったりとか、ずっと小さいときからお菓子作ってたのね。レゴブロックとガンプラのera(時代)が終わったあとはお菓子作りだった。それもあって、お菓子の専門学校行って。上京したかったっていうのもあって、西新宿にあるヒルトン東京っていうホテルに就職した。

◻︎ Why did you decide to pursue pastry-making?

My high school was a college-prep school, and for some reason, I felt rebellious about the expectation that everyone would go to university. Looking back now, I kind of wish I had gone. My parents loved cooking, and I also liked it from a young age – especially making sweets. I used to bake my own Christmas cakes every year and had been making sweets since I was little. After my LEGO and Gunpla era ended, baking became my main hobby. Because of that, I went to a culinary school specializing in pastry. I wanted to move to Tokyo, so I ended up getting a job at Hilton Tokyo in Nishi-Shinjuku.

◻︎ お菓子作りで学んだことは?

最近気づいたのは、お菓子作りしてなかったらこの手仕事(手作業)の素晴らしさっていうか、面白さっていうのは気づいてなかったんじゃないかなと思って。それが一番大きいかな。あと「先の先を考えて今を考える」って例えば、ケーキを焼くときとかも先にオーブン温めておきます、とかそういうの。バイトもずっとレストランのキッチンだったから、そういうのが染みついてるのはあるかもしれない。

でも、それが最近自分の作品を作るうえで弊害になってきてるなっていうのもあって。先に完成形を考えちゃってた。完成する姿が自分のなかでイメージにあって、逆算するように作っちゃってたのね。でもこの間展示した作品はそうじゃなくて、自分でも最後にどうなるかわかんない作品を作りたくって。ちょっと作り方を詳しく説明すると、なにも考えずにランダムに穴を空けて、最終的に穴を空けた2枚のレイアウトをすり合わせることで初めて自分でも想像してなかった像が現れるっていう。座右の銘で「先の先を考えて今を考える」っていうのもあるんだけど、なるべく制作においては離れた表現をしたいなと思ってる。だからそこのバランスを上手くやっていけたらなって感じ。

◻︎ What did you learn from making pastries?

One thing I’ve realized recently is that if I hadn’t done pastry-making, I probably wouldn’t have noticed the value or the fun of hands-on work. That’s probably the biggest thing I gained. Also, the idea of “thinking about the present from the perspective of the future” shows up in baking too. For example, when you bake a cake, you preheat the oven in advance. I also spent a long time working in restaurant kitchens, so that kind of mindset is set in me.

But I’ve also noticed that this approach can sometimes be a drawback in my own art. I used to always imagine the final product in advance and work backward from that image. Recently, though, I wanted to create works where even I don’t know exactly how they will turn out. To explain a bit: I make random holes without thinking too much, then layer and align two sheets with the holes glued together. This produces an image I could never have imagined beforehand. Even though one of my mottos is “think about the present from the perspective of the future,” I try to step away from that in my creative process. It’s about finding a balance between planning and letting the work take its own course.

◻︎ パティシエをやめてカメラマンになったきっかけは?

簡単にいうとインスタグラム。当時インスタが出はじめたくらい。元々お母さんがすごい写真好きだったの。ちっちゃい頃から一眼レフに望遠レンズつけて僕の運動会の写真とか撮ってるような。お母さんからフィルムカメラもらって、いろんな写真を撮ってて。ハッシュタグでさ #写真好きと繋がりたい とか、そういうのつけて投稿してたら友達ができたんよ。SNSとか僕が東京出る前は全然やってなかったから。すごい狭い田舎から出てきて、友達ってこんな簡単にできるんだ!みたいな。

お菓子作るの好きだったし、飴細工とかも好きだったけど、ちょうど同じ時期に外資のホテルの労基が厳しくなって「居残りで飴細工、チョコ細工の練習ダメでーす!」ってなっちゃった。つまんないなってなっちゃって、どんどん写真撮るの面白くなって。たまたまインスタで知り合った写真家の友達が代官山スタジオで勤めてて、その人が「写真本気でやりたいんだったらスタジオ入ってお金もらいながら勉強できるよ」って誘ってくれて。当時写ルンですで撮ってるような写真が流行ってて、こんなん誰でも撮れんじゃんみたいな。僕はもっとロジカルにテクニカルに写真を学びたいなと思ってスタジオに入ったって感じかな。

◻︎ What made you quit being a pastry chef and become a photographer?

Simply, it was Instagram. This was around the time Instagram was just coming out. My mom has always loved photography ever since I was little, she was taking pictures at my sports festivals with a DSLR and a telephoto lens. Eventually she gave me a film camera, and I was taking all sorts of photos. I started posting them with hashtags like #photographycommunity, trying to connect with people who liked photography, and I actually made friends that way. I hadn’t really used social media before leaving home, so coming from such a small rural town, I was amazed at how easily you could meet people.

I loved making pastries and sugar art, but around the same time, the labor regulations at the foreign-run hotels got stricter. They said, “No staying after hours to practice sugar or chocolate work!” That felt frustrating, and I started enjoying photography more and more. By chance, I connected on Instagram with a photographer friend who was working at Daikanyama Studio. He told me, “If you really want to pursue photography, you can join the studio and learn while getting paid.” At that time, disposable-cameras were really popular, and I felt like anyone could use those. I wanted to study photography more logically and technically, so I joined the studio to learn properly.

◻︎ すでにいろいろなキャリアを経験してるけど、30歳になってみての感想は?人生のスタートラインって感じ?

それはね、分かる。楽しいんだよ30歳、楽しいの本当に。結構僕トラディショナルな日本の家系に生まれたから、実際言われたかどうかは覚えてないけど、うちの親としてはフォトグラファーになろうやなんやろうがいいんだろうけど、30までに芽が出なかったら考えなさいみたいなプレッシャーを感じてたの。だからそれまでにちゃんと自分で食っていけるようになろうと思ってやってたけど実際にそうはなんないし、なんなかったんだけど。

今普通に生きていけるし、30になってからのほうが楽しい。20代で培った友人関係とか、蒔いた種の芽が出はじめてる感じがする。周りの同年代で一緒にアシスタントしてた時期に頑張ってた人たちもどんどん30歳ぐらいを境目に大きくなってってて、それだけでも楽しいし。それに負けじと僕も頑張ろうみたいなのもある。

◻︎ You’ve already experienced various careers, but how does it feel to be 30? Does it feel like a new beginning in your life?

I get that. Being 30 is really fun – it honestly is. I was born into a fairly traditional Japanese family, so even if they never said it directly, I felt a kind of pressure from my parents: it was fine if I wanted to become a photographer, but if nothing came of it by the time I was 30, I should reconsider my paths. So I worked hard to be able to support myself properly by then, but in reality, that didn’t really happen.

Still, I can live comfortably now, and life has actually become more enjoyable since turning 30. Friendships I built in my twenties and seeds I planted are finally starting to grow. People my age who were also working as assistants around the same time are starting to make big strides around 30, and seeing that is exciting. It also motivates me to keep pushing myself and not fall behind.

◻︎ 今ハタチ(20代)の子にメッセージを送るとしたら?

いっぱい無茶したほうがいい気がする。みんな言うと思うんだけど、無茶がきかなくなると思うんだよね、30超えて。僕はまだできるけど、簡単な話でいうと二日酔いのしんどさが全然ちがうみたいな。なるべくそういうふうにはならないようにって思ってたけど、プライドってどうしても高くなっちゃうから、失敗するのが怖くなるんだよね。だからいろんなことに挑戦していろんなことに失敗したほうがいいなって。それがその人の人生を豊かにするなとも思うし。いっぱい無茶して、いっぱい失敗してくださいって感じかな。僕がハタチの自分に言えるんだったら。

◻︎ If you could send a message to someone in their twenties, what would it be?

I think it’s important to take lots of risks. Everyone probably says that, but you lose some of that freedom once you hit 30. I can still do it, but even something simple, like recovering from a hangover, is completely different now. I tried to avoid that, but as your pride grows, so does your fear of failure. So I’d say it’s better to challenge yourself, try lots of things, and fail a lot. That’s what makes life richer. Take risks, make mistakes, and learn from them – that’s what I’d tell my twenty-year-old self.

◻︎ 「Hinataくんの先の先」はどういう未来を描いているの?

最終的なゴールはしっかりあって、それは地元でやってる大地の芸術祭っていうアートフェスティバルに携わる仕事をすること。アーティストとして携われたら嬉しいけど、そうじゃなくても携わって地元を盛り上げたいっていう気持ちはすごいあるかな。やっぱちっちゃい頃からアートに触れられてたのはその芸術祭のおかげだし、新潟の田舎でそういう機会を作っているっていうのはすごいことだと思うのね。

ロンドンで写真をやってた先輩が「キャリアの途中からアーティストになることは難しい」って言っていて。それはどうしてかっていう話をしたときに、海外の写真家、アーティストになるような人たちって、ちっちゃい頃から家に絵画が飾ってあったりとか、親に美術館に連れて行ってもらえたりとか、そういう経験があるのがほとんどだから、そういう人には太刀打ちできないと思ったって言ってて。俺はそういう経験あるな、みたいな。

大地の芸術祭ってすごい面白くって。自然、土地を生かした感じで、うちの近所の田んぼに急にドンって作品があったり。それをちっちゃい頃から何気なく見てたし、うちの親もアーティストでもなんでもないけど、美術館に連れて行ってくれてたっていうのもある。大地の芸術祭が僕に与えてくれたものは大きいなって今になって気づいて、だから恩返しがしたいじゃないけど、最終的にはそれに携わることがしたい。

ただ、今やっぱり痛感してるのは、日本のアート業界ってすごいアカデミックっていうか、今いろいろ申請してるけど、やっぱり大学出て美大出てないと相手にもしてもらえない。そこに抗って突き進むのか、こっちで美大に行くのもありだなって思ってるし、先の先を考えて行動はしてるけど、常に選択肢は多くもっておこうかなみたいなことはあるかもね。近い将来の目標は、日本で展示できたらいいなとは思ってるけど、日本のアートレジデンスとかも応募してるけど、受かるかはわかりませんって感じ。

◻︎ What does “the future beyond the future” look like for you?

I do have a clear ultimate goal. I want to be involved with the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale, an art festival in my hometown. It would be amazing to participate as an artist, but even if not, I really want to contribute in some way and help energize my local community. I was exposed to art from a young age because of that festival, and I think it’s incredible that opportunities like that exist in rural Niigata.

A senpai of mine who was doing photography in London once told me, “It’s hard to become an artist midway through your career.” When we talked about why, he said that most successful photographers or artists all over the world grew up with paintings in their homes or were taken to museums by their parents. He felt he couldn’t compete with people who had that kind of experience in childhood. I realized I actually had experiences like that myself.

The Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale is fascinating. It uses nature and the land itself – suddenly, you might see an artwork appear in a rice field near my home. I casually saw things like that growing up, and my non-artist parents would take me to museums. Looking back, I realize how much the festival influenced me, and I want to give back in some way. Ultimately, I’d love to be involved with it.

At the same time, I’ve become painfully aware that the Japanese art world is very academic. I’m applying to various programs, but if you haven’t gone to university or an art school, it’s hard to get taken seriously. I’m considering whether to push forward despite that, or maybe attend an art school here. I do think about the “future beyond the future,” but I also want to keep my options open. My short-term goal is to have an exhibition in Japan. I’m applying for Japanese art residencies as well, but I don’t know if I’ll be accepted.

◻︎ 今はベルリンに住み続けていたい?

そうだね、今はやっと5年住んでベルリンでの人間関係とかも芽が出はじめた感じがするし、コロナでほぼ2年間なんもできなかったっていうのもあるし。来てからしばらくはなんもできなくて、やっとその1、2年後ぐらいに自分の生活の基盤がこっちになったなって感覚があった。引っ越しもいっぱいしたし。家も決まってスタジオももてて、やっと自分のベルリンの生活に集中できる環境が整ったから、もうちょっとこの街で自分がどういうことができるのか、どういうことしたいのかっていうのを、考えてみてって感じかな。

◻︎ Do you want to continue living in Berlin for now?

Yeah, I think so. I’ve finally been here for five years, and it feels like the relationships I’ve built in Berlin are starting to bear fruit. Also, because of COVID, there were almost two years when I couldn’t do much at all. For a while after I arrived, I couldn’t really get anything going, but about a year or two later, I finally felt like my life here had settled. I moved around a lot, but now I have a place to live and a studio, and the environment is finally set up so I can focus on my creative work in Berlin. Now I can really think about what I want to do here and what I’m capable of doing in this city.

| Hinata Ishizawa 1994年、新潟県津南町出身。現在はベルリンを拠点に活動。東京のホテルでパティシエとして勤務したのち、撮影スタジオにてフォトグラファーアシスタントとして経験を積む。2017年より写真家としての活動を開始し、2020年からはドイツに移住、ベルリンを中心に作品制作を行っている。2022年以降は、写真を起点にしながらも、音声データ、Found materialsを用いたコラージュ作品、またプログラミングやAIを用いたインスタレーション作品へと表現を広げ、データ社会における夢や記憶、監視資本主義を主題に制作を行っている。 Born in 1994 in Tsunan, Niigata, Japan. After working as a pastry chef in a hotel, he trained as a photographer’s assistant in a commercial studio in Tokyo. He began working as a photographer in 2017 in Tokyo, and since 2020 has been based in Germany, producing work primarily in Berlin. Since 2022, his practice has expanded beyond photography to include collage works using sound data and found materials, as well as installation pieces incorporating programming and AI. His work focuses on themes such as dreams, memory, and surveillance capitalism within the context of a data-driven society. Instagram: @hnt_ishi Website: hinataishizawa.com |